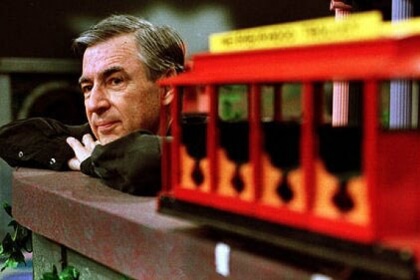

Gene J. Puskar/Associated Press

If you’re old enough to remember Mr. Rogers, you might remember him singing the happy little song, “So, who are the people in your neighborhood, in your neighborhood, in your neighborhood… they’re the people that you meet when you’re walking down the street. They’re the people that you meet each day.”

This isn’t Mr. Rogers’ neighborhood. It’s a lot smaller, but there are some interesting characters here. They are bacteria, also called gut flora, or microflora.

The microflora in the gut are way more important than anyone realized even a few years ago. This microbiome is made up of communities of bacteria and other organisms. Tiny changes here can have big effects — not only on our digestive tract, but on our emotions.

Cynthia Sears, M.D., professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, is the director of the Scientific Advisory Board of the new Johns Hopkins Food, Body & Mind Center. (I wrote about some of the research going on at this center in a recent post.) In addition to finding links between diet and disease, scientists at the Center, particularly Sears, are studying the role of good and bad bacteria in making us sick and keeping us healthy.

Sears has focused on the many interactions between the gut’s microflora – the little ecosystems of bacteria that live and die down there in without our ever knowing about it – and our health. I recently interviewed her for Breakthrough, the magazine for the Johns Hopkins Center for Innovative Medicine. Rapidly expanding evidence, she told me, suggests “that the complex communities that we carry with us, which are on every surface of the body, are essential to health. But they’re also associated with disease” — both right there in the gut, and distantly. “They influence liver function, the function of the deep tissues, the enteric nervous system.” They may also contribute to heart disease, pancreatic conditions, and be linked to our mood and to psychiatric disorders, as well as our weight. “This concept is amazing,” she says, “particularly the idea that they can influence our mood and how we function in life.”

So, imagine that you have depression, and a doctor has put you on an antidepressant. And it’s not really helping that much. Then imagine that a doctor tells you, “the problem could be in your gut.” This discussion is still pretty new, Sears says, but “our hope is that we will be able to identify the bacteria that produce the right metabolites, the ones that make you feel better,” to change how the microbiome functions. “So if the microbiome has bad molecules, that we could modify it or treat it in such a way that you get good molecules and change the balance.”

Photo Credit: sahilsajjad via Compfight cc

I asked her if this might one day eliminate the need for antidepressants. Probably not, Sears says. “But there are a lot of people who probably don’t fit into classic psychiatric criteria, who don’t feel well. So this idea that we can use food and possibly ‘good’ bacteria to modify function and make someone feel better, and help turn someone’s life around, is very intriguing.”

Fermented Foods and Probiotics

Is there anything you can do to help clean up the neighborhood of bacteria in your gut? Well, yes: You can eat fermented foods, which contain probiotics, or you can take supplemental probiotics. The problem with probiotics is that they are not regulated as drugs by the FDA, and there is a lot of variability in quality and effectiveness. Similarly, there is a surprising lack of definitive, scientific journal-published research absolutely proving that fermented foods are helpful to your health. However, that said, there is a lot of anecdotal evidence that they are. The fermented items listed below, eaten in moderation, are not harmful to your health. You may want to give them a shot for a couple of weeks, and see if you feel better with them in your diet.

Sauerkraut. It’s fermented, hip, it’s happenin’ — check out the gourmet varieties (like Wildbrine’s Arame Ginger) of sauerkraut in the refrigerated section at upscale grocery stores — and it’s been around since the 4th century B.C. First of all, it’s cabbage, and cabbage is already good for you, just raw out of the garden. It’s in the family of cruciferous vegetables, along with broccoli and cauliflower, which have long been shown to help prevent cancer. But the fermentation process brings some new chemicals to the table, including: isothiocyanates, which counteract carcinogens and help the body remove them; glucosinolates, which activate the body’s anti-oxidants; and flavenoids, which help protect artery walls. Sauerkraut has few calories. However, if you eat too much of it, it can cause diarrhea. Again, moderation in all things.

Kombucha. Fermented black tea. Again, we’re starting with something that is already good for you; tea is rich in antioxidants. Fermented black tea delivers a load of probiotics to your gut. In addition to aiding digestion, these beneficial bacteria boost the immune system and can relieve irritable bowel symptoms, yeast infections, and other problems. In one study, rats given kombucha had higher levels of “good” HDL cholesterol, a finding linked to a lower risk of cardiovascular trouble. FloraStor, a commercial probiotic that’s used to treat C. difficile colitis, was isolated from kombucha. A study from India found that a form of kombucha was just as effective as the drug, omeprazole (Prilosec), in healing stomach ulcers. (Note: If you have an ulcer, I wouldn’t chuck Prilosec and start drinking kombucha. For one thing, the kind you get might not have the kind of bacteria these scientists studied; also, how much would you need to be drinking every day, and for how long? Ideally, as fermented foods become more popular, they will be better studied and their benefits will become a lot more clear.)

Yogurt. Look for the words, “Live and active cultures.” These are probiotics, and besides increasing the number of good bacteria in your gut, they can help reduce symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, and also can help improve symptoms of inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis. Greek yogurt has more protein than traditional yogurt; it takes longer to digest and can help you feel full longer — which, in turn, can reduce the need for snacks between meals, so as a bonus, it may help you lose weight.

Yogurt. Look for the words, “Live and active cultures.” These are probiotics, and besides increasing the number of good bacteria in your gut, they can help reduce symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, and also can help improve symptoms of inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis. Greek yogurt has more protein than traditional yogurt; it takes longer to digest and can help you feel full longer — which, in turn, can reduce the need for snacks between meals, so as a bonus, it may help you lose weight.

In addition to the book, I have written about prostate cancer on the Prostate Cancer Foundation’s website, pcf.org. The stories I’ve written are under the categories, “Understanding Prostate Cancer,” and “For Patients.” I firmly believe that knowledge is power. Saving your life may start with you going to the doctor and knowing the right questions to ask. I hope all men will put prostate cancer on their radar. Get a baseline PSA blood test in your early 40s, and if you are of African descent, or if cancer and/or prostate cancer runs in your family, you need to be screened regularly for the disease. Many doctors don’t do this, so it’s up to you to ask for it.

©Janet Farrar Worthington