Got irritable bowel? As many as 40 percent of people who go to the doctor with gastrointestinal problems suffer from irritable bowel syndrome (alternating diarrhea and constipation); dyspepsia (uncomfortable fullness or pain in the upper abdomen, heartburn, or other digestive problems); or gastroparesis (the stomach muscles or the nerves that drive them stop working, and food doesn’t move out of the stomach the way it should).

These conditions are motility disorders, and they involve the enteric nervous system, the massive highway of nerve cells lining the muscular walls of your esophagus, stomach, intestines, and rectum. The enteric nerves control peristalis, the conveyor-belt series of muscle contractions — think of toothpaste being squeezed through a tube — essential for swallowing, for digestion, absorption of food, and for pooping (literally, movement of the bowels).

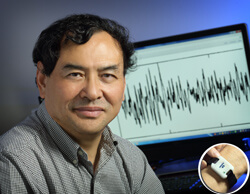

“The treatment of motility disorders really requires the art as well as the science of medicine, because every patient responds differently,” says Pankaj Jay Pasricha, M.D., gastroenterologist and neuroscientist, director of the Center for Digestive Diseases at Johns Hopkins Bayview. Pasricha created the Johns Hopkins Center for Neurogastroenterology and Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders to explore this gut-brain axis, which I wrote about here.

Diagnosing and treating these disorders can take time, dedication, creativity, and patience. My husband, Mark, an excellent gastroenterologist, was on the faculty at Johns Hopkins and the University of Virginia before he went into private practice here in his home state of Arizona. Many of his patients have difficult diseases, and he works with them – sometimes for months or even years – to find the right treatment to improve their lives. By the time they get to him, these patients may be feeling frustration or even despair because they haven’t gotten the help they need. For years, irritable bowel was the fibromyalgia of GI disorders, misunderstood and misdiagnosed. If you are suffering from irritable bowel symptoms, you probably already know this. Maybe you’ve also had a doctor get frustrated or impatient with you when you didn’t get better – like it’s your fault, or it is all in your head! Or maybe the doctor has done a colonoscopy or endoscopy and, not finding anything striking, has seemed to lose interest in your care. You’re not alone.

Successful treatment starts with a meticulous history and careful physical exam. “About 80 percent of the time,” says Mark, “the key to the diagnosis is right there in the history.” But just knowing the underlying cause of a motility disorder doesn’t necessarily mean the problem can be fixed right away. Everybody’s different, and there is no cookie-cutter approach to making this better; treatment that helps one person won’t necessarily help someone else with the same diagnosis. “If we’re trying a new medicine, it can take four weeks, or longer, to see if it works,” says Mark. “And if it doesn’t, then it’s another several weeks with the next medicine, and the next. There’s a lot of trial and error, but if the doctor and patient are determined, and if they have patience to keep trying, we can often make it better. The art is managing the symptoms, such as diarrhea, without simply converting it to chronic constipation, which is just as miserable in its own way.”

Not all treatment requires a prescription: There are some very good over-the-counter products that can help reduce symptoms. (Note: Heartburn and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), and acid reducers and proton pump inhibitors, are discussed here.) Here are four: For dyspepsia, Mark often recommends FDgard, whose ingredients include peppermint oil and caraway oil. For irritable bowel, IBgard is a similar product — except it works in the gut, instead of the stomach. Iberogast, an herbal medicine from Germany, works on both the stomach and gut: just put 20 drops into a glass of water or tea. Equalactin helps ease irritable bowel by evening things out: it treats constipation by adding bulk and also increasing the amount of water in your poop, making it easier to pass; at the same time, the bulking agent treats diarrhea by making it less runny and more solid.

What else? You may need to take a good, close look at your diet. “Foods can be a major issue,” says Mark. “Many people have food allergies and don’t know it, and the way we figure this out is to remove one type of food (like dairy products) from the diet at a time and see if it makes a difference. Celiac disease is not an allergy but an immune reaction to gluten, and the treatment is a gluten-free diet, which is harder than you may think,” because many products, from soy sauce to shampoo, have wheat. Shampoo?? Yes, and to people with celiac, or people who are very sensitive to gluten, even absorbing it through the skin can cause cramping, bloating, and diarrhea. If you have a food allergy or celiac disease, “you need to change the diet permanently to get lasting relief. This requires a commitment,” and vigilance to check every single label of every packaged food you buy. It also requires discussions with the server at every single restaurant you go to. This can get old – trust me; in my family, in addition to GERD and irritable bowel, we’ve got celiac disease, lactose intolerance, and an allergy to milk and butter (from cows, but not from goats; go figure!). It’s a pain, but the consequence of not being vigilant about what my family members eat is sickness. In the case of celiac disease, prolonged exposure can actually lead to cancer in the small bowel — but prolonged avoidance of gluten means a healthy life! It’s a no-brainer.

“Many patients have a sensitivity to FODMAPs, which are fermentable things in foods we eat.” Every time I hear the word, “FODMAP,” I think of the old song, “RaggMopp,” by the Treniers. Just putting that out there. FODMAP is an acronym for Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, Mono-saccharides And Polyols. And what are these fine fellows, you may be wondering? Basically, they’re carbs. Notorious carbs that may not do villainous things to other people, but if you are sensitive to them, they trigger bloating, gas and stomach pain.

The key word here is fermentable: Sugars, sugar alcohols, high-fructose corn syrup, lactose, sugars in fruits, especially stone fruits (pears, plums, peaches, prunes, and probably some others that don’t start with the letter p). “All these foods tend to make everyone produce gas, but the effect is greater on people who have irritable bowel,” says Mark. Basically, if you have irritable bowel, these foods are a fermentable toot fest.

So that’s the F in FODMAP; what about the other letters? Oligosaccharides are foods including wheat, rye, legumes, garlic, onions, and some other fruits and vegetables. Disaccharides are milk, yogurt, and soft cheese. The sugar they contain is lactose. Monosaccharides have a different type of sugar, fructose, and include fruits such as figs and mangoes, agave nectar and honey. Polyols are found in other fruits and vegetables, including blackberries. They’re also found in sugar-free gum.

The bottom line here, no pun intended, is this: If you find that you have a lot of gas and discomfort after eating, if you are prone to diarrhea, constipation, or both, if you are feeling like food is not moving through your GI tract the way it ought to, well, it’s quite possible that you have a motility disorder such as irritable bowel. The good news is that there is help out there — prescription medicine, over-the-counter treatment, and dietary changes.

©Janet Farrar Worthington

This is what doctors at the Amos Center for Food, Body & Mind at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center want to know.

This is what doctors at the Amos Center for Food, Body & Mind at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center want to know.

It’s important to remember that “the microbiome is just part of the study,” Harer continues.

It’s important to remember that “the microbiome is just part of the study,” Harer continues.

Imagine:

Imagine: