Medicine wears off. If you take a pill, its benefit might last for 12 or even 24 hours, and then you have to take another one. The same holds true for acupuncture. Although administered differently – inserting very thin needles through your skin at strategic points – its effects tend to fade just as quickly.

There’s one big difference: Most people who get acupuncture only have it once or twice a week, at most. Imagine if you had an antibiotic that worked, and you only took it once a week.

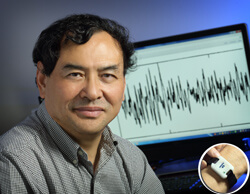

Courtesy of Johns Hopkins Medicine

Jiande Chen, Ph.D., a Johns Hopkins biomedical engineer working with the Amos Food, Body, and Mind Center, is about to change this. I interviewed him recently for Breakthrough, a magazine for the Johns Hopkins Center for Innovative Medicine.

Chen specializes in the pathophysiology of gastrointestinal motility – how food moves through your body — as well as diabetes and obesity. He is particularly interested in electrical therapies that stimulate the nerves involved in gut function, and now he has developed a novel device for patients to use at home that provides “transcutaneous electrical stimulation” similar to the effect of acupuncture.

In other words, he’s developed a smart watch for acupuncture.

Requiring only a watch battery, it delivers a painless, noninvasive dose of electric current that penetrates as deeply and precisely as one of those long, thin needles. But patients can administer it themselves, at home, after every meal.

It’s safe, DIY home acupuncture, and it might significantly change the way people with certain conditions, starting with gastroparesis, find relief.

In gastroparesis, the stomach is slow to empty. Food lingers because the muscles that should move it along to the gut – squeezing it like toothpaste through a tube – are either damaged or weak. One big cause is diabetes. The condition can be miserable and can include decreased appetite, heartburn, nausea, vomiting, bloating, anxiety, and discomfort. Symptoms are usually treated with medicine and dietary changes, but in a recent study, Hopkins scientists showed that acupuncture can also help relieve symptoms.

Now, let’s switch for a moment and look at gastroparesis as an acupuncturist would. In traditional Chinese medicine, a complex system of healing more than 5,000 years old, practitioners believe our vital energy, called “qi” (pronounced “chee”), flows through the body along 12 pathways, called meridians. Each meridian involves a different organ system.

When all is well, the qi flows smoothly; but when there is an imbalance somewhere, the flow is blocked or hindered, and that’s how disease can begin. The needles inserted during acupuncture are designed to restore this balance. Gastroparesis might be called “food stagnation,” or “liver and spleen disharmony” in Chinese medicine, but the basic problem would be the same: food not moving through the digestive tract. The liver is supposed to ensure that everything – digestion as well as emotions – flows smoothly. When this flow is blocked, it weakens the spleen, which is in charge of digestion.

Acupuncture stimulates nerves – in this case, the vagus nerve, which reaches all the way from the brain down through the esophagus, heart, and lungs, down to the abdomen, and controls many things, including digestion. It also stimulates blood flow by dilating blood vessels and causes the body to release endorphins, natural painkillers.

In someone with gastroparesis, acupuncture sends a signal to the brain via the vagus nerve, telling the stomach to work better.

Chen’s device works by neuromodulation, using electrical stimulation to change how nerve cells interact. In painstaking research, he has determined the precise levels needed to produce a beneficial change in the function of the nerves – how much energy to release, the speed of the electrical signal, the width of the pulse.

That precision “is one difference between our method and traditional Chinese medicine.” Another is frequency: “It would be very expensive to do traditional acupuncture two or three times a day, but with this device, you are just putting an electrode at the acupuncture points. You could do it after every meal.”

There are two key placement points: One is the wrist, “which is very good for treating symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and motion sickness. That wrist acupuncture point is very close to the medial nerve.” The other is about 5 centimeters below the knee, a place called “stomach point number 36” in acupuncture. “This is very close to the perineal nerve,” and stimulation here “is known to enhance the autonomic nerve function, which helps empty the stomach and improves the digestive process.”

Basically, Chen explains, “We combined modern neuromodulation theory with traditional Chinese acupuncture.” This is just the kind of project its leaders envisioned when the Amos Food, Body, and Mind center began a year ago: blending Eastern medicine with state-of-the-art technology in a holistic, whole-body approach to improving health.

The device has not yet received FDA approval and it doesn’t work for everyone, Chen notes, “but our results of early studies are very exciting.” In related work, Chen plans to see whether the device can help improve symptoms in patients with scleroderma and whether it can help reduce the appetite in people with obesity.

©Janet Farrar Worthington