So Simple, But Does the Paleo Diet Make You Feel Better?

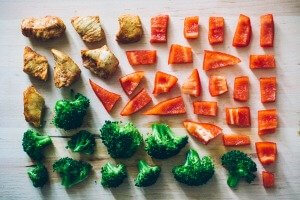

Does the Paleo diet, basically, eating lean meats, nuts, fresh fruits and vegetables – foods our Stone Age, hunter-gatherer ancestors could have eaten – really make you feel better?

If it does, then why? And how, exactly?

What happens to the microbiome – the countless bacteria that live inside the gut – when you stop eating dairy, processed sugars and carbs?

This is what doctors at the Amos Center for Food, Body & Mind at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center want to know. Some of their patients who have irritable bowel syndrome (characterized by constipation, diarrhea, and nausea, it also can include anxiety or depression) have reported that they have been doing better after changing to a Paleo diet.

This is what doctors at the Amos Center for Food, Body & Mind at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center want to know. Some of their patients who have irritable bowel syndrome (characterized by constipation, diarrhea, and nausea, it also can include anxiety or depression) have reported that they have been doing better after changing to a Paleo diet.

To help find out why, Kimberly Harer, M.D., gastroenterology fellow at the Center, designed a short-term study. I recently interviewed Harer and her colleague, epidemiologist Noel Mueller, Ph.D., for Breakthrough, a publication of the Center for Innovative Medicine at Johns Hopkins.

For two weeks, she says, 40 patients with IBS will be randomly assigned to eat either a Paleo diet or a standard, healthful diet. Harer and Mueller will be looking at many things in these study participants, including “how the diet affects their GI symptoms, their quality of life, their vitality,” says Harer. In people who have been experiencing anxiety or depression, the investigators will look for changes in these symptoms, as well. They will study blood samples and patient responses to questionnaires about their health, and then, looking at the bacteria in stool specimens, the scientists will analyze the gut “microbiome” before and after.

Let’s just take a moment to reflect on the concept – still fairly new in research – of a microbiome: It’s a small ecosystem made up of bacteria; this is more complex than it sounds. Just as the earth has its own ecosystems – tundra, tropical rainforests, grasslands – your body has them, too. Except instead of plants, these microbiomes are populated by bacteria: dozens of them, picky little cliques that only thrive in one particular spot. For example, the bacteria on the inside of your elbow are different from the bacteria on your face – and even on your face, the bacteria on the bridge of your nose are different from the bacteria between your nose and mouth; and those bacteria are different from bacteria on your chin.

But the gut takes it to another level; it is the microbial mother lode. In numbers alone, it’s intimidating. “There are trillions of microbiota (tiny habitats) in the gut,” says Mueller. And get this: All of those bacteria in all those micro-habitats have their own genes and their own genomes, which scientists now know how to sequence. “There are 100 to one more microbial genes than in your own human genome.”

This is why scientists at the Amos Center are convinced that the microbiome has an important influence on our health. It’s not just numbers, it’s sheer mass: All those bacteria that live inside our gut, if you somehow got them all together in one lump, would weigh and take up about as much space as your brain – three or four pounds. Trying to get a handle on that would be overwhelming without sophisticated computers and software, sequencing technology, and bioinformatics tools that allow scientists to recognize patterns and identify gene signatures.

This is why scientists at the Amos Center are convinced that the microbiome has an important influence on our health. It’s not just numbers, it’s sheer mass: All those bacteria that live inside our gut, if you somehow got them all together in one lump, would weigh and take up about as much space as your brain – three or four pounds. Trying to get a handle on that would be overwhelming without sophisticated computers and software, sequencing technology, and bioinformatics tools that allow scientists to recognize patterns and identify gene signatures.

Because the study of the gut’s microbiome is still so new, nobody is sure what it’s supposed to look like, and how the gut flora relates to symptoms. “Maybe we won’t ever be able to define what is the normal gut microbiome,” says Mueller. “Normal might be different for everybody.”

Even in identical twins, Mueller continues, the bacteria in the gut can be very different. It is not unheard of for one twin to have a normal weight, and one to be obese.

Already, at many hospitals gut doctors are waging war with bacteria, successfully treating patients who suffer debilitating diarrhea from recurrent Clostridium difficile (C.diff) colitis with fecal microbiota transplants. Basically, uninfected fecal material from a relative with healthy gut bacteria is inserted into the patient’s colon, the good bacteria overwhelm the bad bacteria and the C.diff. is conquered.

In mice, Mueller notes, scientists have found that if they take the microbiota from the fecal sample of an obese individual and inject it into a germ-free mouse, that germ-free mouse will start to become overweight, too. “The phenotype of obesity can be replicated just through the sharing of bacteria,” he says. There is a lot of evidence to suggest that gut bacteria play a huge role in diseases of the metabolism – which also suggests that if these bacteria can be changed, there is great potential to improve someone’s health.

In this study, says Harer, “we will look at the microbiome at three different time points. First, the baseline, before the diet changes; then, after the Paleo or study diet.” And then one more time: after participants go back to eating whatever they used to eat for four weeks. Blood samples will be taken after that four-week period, as well, and patients will fill out questionnaires to report any change in their symptoms.

“If there are differences in the blood and the stool samples, it will be interesting to see if those correlate with changes in their symptoms,” says Harer. “And we are very interested to see whether reverting back to their old diet causes the former symptoms to come back, or whether there are lasting changes.”

Certain families of bacteria thrive on a diet full of macaroni and cheese, soda, and ham sandwiches. Entirely different bacteria could show up if that diet changes to lean meat, nuts, berries, and veggies. Which raises another question: If someone gets better with the Paleo diet, “what part is the beneficial part? Is it the lower carbs? Is it the increase in plants, or in protein content? Is it cutting out gluten?” Or is it some new, beneficial bacteria that have taken precedence in the gut?

It’s important to remember that “the microbiome is just part of the study,” Harer continues. “The question is, does this diet improve symptoms in IBS patients? Unfortunately, there is a huge unmet need in these patients, because there are few effective treatments.”

It’s important to remember that “the microbiome is just part of the study,” Harer continues. “The question is, does this diet improve symptoms in IBS patients? Unfortunately, there is a huge unmet need in these patients, because there are few effective treatments.”

Many people who have IBS are not treated very thoughtfully; they get laxatives for constipation, medicine for diarrhea, and often the symptoms don’t go away because the underlying cause is still there. The Amos Center takes a team approach with gastroenterologists, allergists and immunologists, psychiatrists, nutritionists, and scientists. Sometimes, Harer says, people who come to the Center are “frustrated, at the end of their rope sometimes when they come to see us. We use everyone’s input to treat them holistically, and also to try new things.”

One of these new things is a diet so simple that – as the commercials put it – “a caveman could do it.” If the Paleo diet does indeed help make people with IBS feel better, understanding why it works at gut level is something we’re only beginning to have the scientific knowledge and tools to decipher.

©Janet Farrar Worthington

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!