Close to Home. Again.

Why do I write so much about prostate cancer? Because I can’t get away from it. And now prostate cancer, never very far away, has hit close to home. Again.

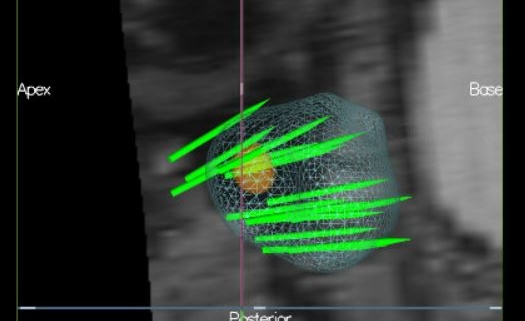

Before I tell you my story, please study this picture. This is a picture of a miracle. It’s not a pincushion. It’s an MRI of a prostate, and the needle biopsy that used this MRI image to find its target – the spot of cancer in what’s ordinarily the most difficult-to-reach, out-of-the-way spot possible. Those green needles aren’t all in there at the same time; this just shows where the needles went. Two of them went directly into that spot of cancer. Believe me when I tell you – as four of the most respected urologists in the U.S. have told me – this cancer would have been missed with the traditional transrectal biopsy, which uses ultrasound. More about this in a minute. The cancer is aggressive – Gleason 9. But it is very small. It is curable, the urologists all believe. I believe it, too.

That’s my husband’s prostate. At this very moment, we are scheduling surgery to get it taken out.

I feel like I’ve been in training for this moment for 28 years.

That’s when prostate cancer made its first unwelcome entrance into my life – when my father-in-law, Tom, died of it at age 53. My husband, Mark, was a medical Chief Resident at Johns Hopkins at the time, and all he could do for his dad was make sure his terrible pain was controlled. Tom never had a chance; he had gone to see the doctor for back pain. That turned out to be prostate cancer, which had already invaded his spine. Tom never had a PSA screening test; nobody did back then. That would change in a couple of years.

I worked at Hopkins, too, as the editor of the medical alumni magazine. When Tom had been diagnosed, his doctor told him, “Don’t worry about it. Prostate cancer is an old man’s disease – the kind you can live with for years.” Tom died within months of his diagnosis. I wanted to know how a 53-year-old man could die of an old man’s disease, so I decided to do a story about prostate cancer. I set up an interview with Patrick Walsh, the head of urology at Hopkins, and we wrote a story that would change my life forever. That sounds kind of melodramatic, but it’s true. I have been writing about prostate cancer ever since.

Back then, I had no idea that Pat Walsh was the surgeon who invented the nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy, and that he had developed the best prostate cancer research and treatment program in the world at that time. I wrote about Tom’s battle with cancer, and Walsh’s operation, and the research that was happening at Hopkins. In those pre-internet days, we were inundated with requests for reprints. Some 3,000 reprints later, we decided to write our first book.

That book was called, The Prostate: A Guide for Men and the Women Who Love Them. We wrote it for women as well as men, because in Walsh’s experience, it was the women who got their men – fathers, husbands, brothers, sons – to the doctor. I found this to be true: as we were writing it, in 1992, I told both my parents that my dad should go to the doctor and get his prostate checked, and he should get this new thing called a PSA blood test. My mom made him go and keep going every year. He hated it, especially the rectal exam, but he went.

In 1997, when Dad was 63, his doctor felt something suspicious on his prostate – a rough patch. “Probably prostatic calculi” (the prostate’s version of tiny gallstones), he said, but he ordered a biopsy, done by Dad’s local urologist in South Carolina. A pathologist found prostate cancer. My parents called me. I called Pat Walsh about 30 seconds later. We sent the slides to Hopkins for a second opinion, and they were read by a world-renowned urologic pathologist, Jonathan Epstein. Two months later, Pat Walsh took out my dad’s prostate, and saved his life. Dad had initially been diagnosed with Gleason 6 (3 + 3) disease, but – like many men – he actually turned out to have some slightly higher-grade cancer, and his pathologic stage was Gleason 3 + 4.

Note: My dad never read my book. My mom did, and on the eight-hour drive up I-95 to Baltimore for the surgery, she read aloud passages of the book she had highlighted.

A few years later, Mark’s grandfather, Charles, died at age 85 of complications from radiation therapy for – you guessed it, prostate cancer. Radiation was not nearly as precise back then as it is now, and there were a lot of complications, particularly in the rectum. Frankly, I don’t think he even needed to be treated; at his age, with heart problems, he could have done watchful waiting – the precursor to active surveillance back in the day.

A few months after that, my beloved grandfather, whom we all called Pop, died. Of a heart attack after being put on a great big dose of estrogen – another treatment they didn’t have the hang of back then – for prostate cancer. Like Mark’s grandfather, Pop was in his eighties, had no symptoms, and probably didn’t even need to be treated. We know so much more now.

Patrick Walsh and I kept writing books on prostate cancer, and our first book morphed into a more cancer-focused book, Dr. Patrick Walsh’s Guide to Surviving Prostate Cancer. Over the years, the news got better and better – particularly the chapters on advanced and metastatic prostate cancer. When we first started, the news there was bleak. Now, in large part due to research funded by the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF), for which I am proud to work as a science writer, there is more hope for treating advanced prostate cancer than ever before. But, as my dad’s case has shown, there’s a lot to be said for early diagnosis and treatment. Ideally, Walsh and I wrote, prostate cancer will be a blip on the radar screen – it’s caught early, it’s treated, and then it’s gone, and you get on with your life. Many men with low-grade disease may never need treatment; they can be safely monitored for years.

When Mark reached age 40, I made sure he got his PSA tested every year. His PSA was very low (less than 1, and then right around 1) when he was in his forties and early fifties. Because of his family history, I told him and his doctor about getting a genetic test (which I have written about) to screen for 16 mutated genes known to be linked to aggressive cancer. Mark took the test, and thank God, it was negative. His PSA went up to 2, so his doctor ordered another test three months later. It was 3. We took another test; also 3. I had suggested to Mark and his doctor that he get the prostate health index (PHI) test, which looks at different types of PSA. Mark’s free PSA had dropped from 25 down to 18 – not encouraging. As we said in our book: free PSA of 25 and above is more likely to be free of cancer.

I called Pat Walsh. He told Mark to come to Hopkins.

We live in a small town in Arizona. Our internist said, “at least get the biopsy done here.”

I said these words: “Absolutely not. You need an MRI.”

I knew this for several reasons: I had written about it from interviews with respected urologists including Bal Carter, of Hopkins; Stacy Loeb, of New York University; and Edward (Ted) Schaeffer, of Northwestern. And I had interviewed Rob Gray – a young guy with a young family, whose battle-scarred prostate had endured multiple ultrasound-guided biopsies, all negative, but whose PSA had continued to go up. His doctors told him not to worry about it; Rob worried. He would still be worrying today, except he had a fusion MRI, which combines several different ways of looking at the prostate. Because of all his other biopsies, his prostate had developed scar tissue that masked the cancer. The MRI found it.

That stayed with me. Then, just weeks ago, I interviewed Hopkins urologist Michael Gorin about two things in particular. One is multi-parametric (mp) MRI, which is similar to fusion MRI, but it’s what they call it at Hopkins. Gorin has developed software that allows him to take the findings of mpMRI and use them as a road map to guide the biopsy.

The other thing Gorin is doing is getting to the prostate by a different approach: through the perineum. The perineum is the area between the scrotum and the rectum.

The traditional transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) biopsy, as its name suggests, reaches the prostate through the rectum. There are a lot of problems with the TRUS biopsy. Because it goes through the rectum, there is a risk of infection. There is no risk of infection from the perineum; in fact, they don’t even give antibiotics for this approach. And, most worrisome about the transrectal approach: it’s hard to cover the entire prostate. This is a problem especially for African American men, who tend to develop prostate cancer in the anterior region of the prostate. Basically, as Ted Schaeffer, an excellent surgeon and coauthor of the book, explained, if you think of a prostate as a house, the transrectal biopsy comes in from the basement. It’s pretty good at reaching the main floor, but not that great at reaching the attic. It’s a South to North approach.

The transperineal approach goes from West to East, and instead of a house, Mike Gorin uses the analogy of a car: the needle comes in from the headlights to the tail lights, but it can go lower, from the front tires to the back tires, or higher, from the front windshield to the rear windshield.

Now, combine this approach with MRI, and it’s a whole new world for diagnosis.

Compared to MRI, TRUS is blind. It’s lame. There, I said it. Imagine you’re playing paintball at night, and you’re trying to hit a target. You do the best you can, but you miss a lot. Then the other team comes in and cleans your clock – because these guys have night-vision goggles. They can actually see what they’re trying to hit. MRI gives the urologist night-vision goggles.

When Mark got his MRI, it showed a 6 mm lesion – a spot the size of a smallish pearl on a necklace. There was a 70-percent chance that this would be cancer. Gorin took that MRI and used it to guide the biopsy. Out of 15 cores taken throughout the prostate, he took two samples from inside this spot; he had a target to hit, and he nailed it. He is my hero.

I’m telling you this because I have learned some things that I want you to know. In fact, like the Ancient Mariner in the very old poem by Samuel Coleridge, I feel compelled to tell you this, and I hope you will feel bound to listen. And I hope to God that someone else will be helped by what I’ve learned, including:

Every patient needs a treatment warrior. An advocate. Mark is an incredibly smart doctor, but he was just as stunned at having a possible diagnosis of cancer as any other patient. His internist wanted him to go to the local urologist for a biopsy. Our small town is not up on all the latest technology. We don’t have an MRI for prostate biopsies. They don’t do the transperineal approach. Again, I am certain that if Mark had gotten the traditional TRUS biopsy, this would not have been found. The lesion on his prostate was in the anterior region – hard to reach, especially if the doctor can’t see and doesn’t have an MRI-revealed target to try to hit. But Mark would have done as his doctor suggested, because he was stunned and he didn’t know as much as I happen to know about prostate biopsies, because his area of expertise is digestive diseases, not prostate cancer.

The difference between ultrasound and MRI is night and day. It’s life-changing, and life-saving.

There is no safe PSA number above 1, as Bal Carter has said for years, and as we say in Chapter 4 of our book. My dad’s PSA was very low: only 1.2. And yet, he had Gleason 3 + 4 disease. Mark’s PSA is only 3. Please understand this point. This may be the most important of all. I have talked to so many men over the last nearly three decades. So many men who were wrongly assured by their doctor – because their doctors did not know better– that “Your PSA is going up, but it’s still pretty low. Don’t worry about it.” If your PSA is going up, worry about it. It may not be cancer, but you have to check. If your doctor sees one PSA reading and judges the number by itself, that doctor is not giving you the best advice.

You must look at PSA velocity: the rate of rise of PSA over time. I will be covering this in more detail in the next post.

And finally – again, because I have written about this disease for nearly 30 years, and talked to so many men with every stage of prostate cancer – the doctors who urge men not to get tested, who tell them not to worry about it, who say there’s no benefit to getting screened for prostate cancer, that the risk of complications from biopsy are too great, that too many men are overtreated, are just plain wrong.

As urologist Stacy Loeb told me: “A diagnosis of prostate cancer doesn’t mean you need to get treated.” But you should be the one to make that decision; don’t let cancer make it for you. Not all men need treatment. Because of Mark’s family history and his Gleason score, even though the one spot of cancer is very small, we will be getting treatment. Surgery. I say we, because it’s both of us. We’re a team.

Mark is worried about the main complications of surgery – temporary urinary incontinence and the risk of erectile dysfunction (ED). Of course he is; nobody wants these complications.

I’m not. There is a huge difference between dealing with the side effects of treatment for localized disease – cancer that is confined within the prostate, cancer that can be cured with surgery or radiation – and the side effects of treatment for advanced disease, treatment that begins with shutting down the male hormones.

The complications from surgery can be treated, and as Pat Walsh says, “Where there’s a will, there’s a way.”

“But what about incontinence?” I don’t care. I know that it’s almost always temporary, and if not, biofeedback is wonderful, and he can start doing the Kegel exercises now. Absolute worst-case scenario, there’s surgery to get an artificial urinary sphincter. We’ll deal with it. It will be okay.

“But what about ED?” I don’t care. We’ll deal with it. There are many treatments, starting with drugs. Worst-case scenario, there’s surgery: a prosthesic implant. I don’t think this will happen; the cancer is nowhere near the neurovascular bundles, the nerves responsible for erection (discovered by Pat Walsh, who developed the “nerve-sparing” radical prostatectomy). I think he will be just fine.

What matters is him being there for me, our son in high school, our son who just graduated college, and our daughter and son-in-law, who are about to have their first baby. That’s all I care about. Mark not being there is unthinkable. Right now, the score in our family is prostate cancer 3 (Tom, Charles, and Pop), our family (my dad, who is about to celebrate his 84th birthday) 1.

I don’t want prostate cancer to win against our family ever again.

When Pat Walsh called with the biopsy report, it took a second to shift from “Oh, my God,” to “Let’s roll.” We had been praying for low-grade cancer, Gleason 3 + 3, but this high-grade; it is aggressive. So we are now dealing with high-risk cancer. But it is small-volume, thank God! Because it was detected early.

“Thank God,” Walsh agreed. “We could not have found it any earlier,” and without MRI, it wouldn’t have been found at all. “These are the lesions we consistently missed” with TRUS biopsy. He explained that where Mark’s tumor is, in the posterior apex of the prostate, is like the nose cone of an airplane. It’s behind the urethra; almost impossible to reach through the rectum – but Gorin reached it through the perineum. One more thing, Walsh said: “It was found with a new machine that Mike Gorin has had only for a week. This was truly a targeted MRI.” Thank God! Now let’s roll.

Note: This MRI is shown with Mark’s permission. He, too, has made it his mission to help men get screened for prostate cancer, and if they have a rising PSA, to get it checked out.

Update: Apparently, the strength of the magnet in the MRI matters a lot. The stronger the magnet, the stronger the image. The prostate MRI magnet used for Mark is 3 Tesla.

In addition to the book, I have written about this story and much more about prostate cancer on the Prostate Cancer Foundation’s website, pcf.org. The stories I’ve written are under the categories, “Understanding Prostate Cancer,” and “For Patients.” As Patrick Walsh and I have said for years in our books, Knowledge is power: Saving your life may start with you going to the doctor, and knowing the right questions to ask. I hope all men will put prostate cancer on their radar. Get a baseline PSA blood test in your early 40s, and if you are of African descent, or if cancer and/or prostate cancer runs in your family, you need to be screened regularly for the disease. Many doctors don’t do this, so it’s up to you to ask for it.

©Janet Farrar Worthington

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] did I say that no PSA number above 1, by itself, is a guarantee that you don’t have cancer? Why do we say […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!