PSA Velocity: It’s Not the Number, but What It Does!

Why did I say that no PSA number above 1, by itself, is a guarantee that you don’t have cancer? Why do we say this in our book?

Because that’s what H. Ballentine (Bal) Carter, M.D., the great Johns Hopkins urologist and scientist, discovered. In fact, he says: “There is no PSA value below which you can guarantee someone they don’t have prostate cancer,” and no value that automatically means it’s cancer. “There are men with PSAs of 20 who don’t have prostate cancer, and men with 0.5 to 1 who can have very serious prostate cancer.”

So, basically: Your PSA number, by itself, means Jack. What happens to it over time means everything.

This is called PSA velocity. It is a concept pioneered in the 1990s by Carter, working with Patrick Walsh, M.D., my co-author on many books and publications, and it’s a very effective way to detect prostate cancer. I recently interviewed Carter, who retired this summer after 32 years at The Brady Urological Institute at Johns Hopkins, for Discovery, a magazine published by the Brady. He devoted his career to making sense of PSA, and what he has accomplished is incredible. Among many findings, Carter also came up with median PSA numbers based on age, which we will discuss in a minute.

It’s a shame that many doctors, including even some urologists, don’t seem to grasp these simple and very effective ideas, and instead focus on the PSA number itself – an idea that was outdated 20 years ago.

I say this because I don’t know how many times I have talked to men who say:

“My doctor says I don’t need to worry about screening for prostate cancer until I’m in my 50s, and even then, it’s not really that big a deal.”

And, “My doctor says my PSA number is low, so everything’s fine, I don’t need to worry about it.”

This makes me very frustrated. I’ve written about the travesty that happened in prostate cancer screening here, so we won’t go into that now.

Let’s get back to Bal Carter and PSA, and let’s time-travel, very briefly, to the late 1980s, when widespread screening for prostate cancer did not exist. The discovery of PSA (prostate-specific antigen, an enzyme made by the prostate) had just made it possible, for the first time, to learn about prostate cancer from a blood test – but nobody knew what to do with PSA, or how to use it along with the rectal exam and the new use of transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy in diagnosing prostate cancer early.

“There was controversy about even using PSA,” Carter recalls. “There were voices saying, ‘Beware, we’re going to uncover a lot of cancers that never should have come to light.’” And that was true. So then came controversy over the PSA threshold: what was the magic number that would indicate the need for a prostate biopsy? “In retrospect, that was probably the wrong thing to be asking,” Carter says. “There was just not a good understanding then of PSA as a continuum.”

Carter pioneered the concept of PSA velocity – the rate at which PSA rises over time. “But that’s never been tested as a screening tool. I honestly believe if we had not focused on a single, absolute threshold, and instead had focused on changes in PSA to alert us that someone has an aggressive cancer, in the long run we may have identified more individuals with the cancers that need to be treated, and eliminated more who don’t need to be treated. But that will require a carefully done, prospective trial.”

Carter started looking at this years ago, in studies that would lay the foundation for PSA screening and also for safe, vigilant active surveillance as a mainstream treatment for low-risk prostate cancer. How that came about, he says, “was really the brilliance of Pat Walsh. When I first joined the faculty, he came to me and said, ‘What do you think would happen if we looked at changes in PSA?’ I said, ‘I think they’ll probably rise faster in people who have prostate cancer. How can we study that?’ And he said, ‘Have you ever heard of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA)?’” The BLSA was conceived in 1958, when gerontologists at the Baltimore City Hospitals were trying to find a better way to study aging. At that time, and even today, scientists would compare men and women who were in their twenties to people who were decades older. But these scientists had a better idea: to revisit the same person every two years, with a history and physical and blood samples that were stored. This made it possible to look at men who had prostate disease, benign enlargement, or localized or metastatic prostate cancer – and then work backward, describing the changes in PSA, over the previous 20 to 30 years.

“I had never heard of it,” Carter continues. “He said, ‘I know they have a large frozen serum bank, and we might be able to use some of that to look at the question: do PSA levels rise faster in men who have aggressive disease vs. men who don’t have prostate cancer?’ Sure enough, that’s the way it turned out.”

Carter’s work, Walsh says, “has changed the way prostate cancer is treated today around the world.” Although Carter is a fine surgeon, “he has done his best not to operate on men who don’t need it. He was a voice of reason at a time when the diagnosis and treatment of the disease underwent revolutionary changes. With the introduction of widespread PSA testing in 1990, the diagnosis of prostate cancer reached epidemic acceleration and led to abuses fed by the greed of many fellow urologists. Those are tough words, but there is no other way to explain it. Bal emphasized the harm of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, proposed solutions based on improved screening practices, and developed guidelines for identifying men who should not be treated. He began by learning about PSA.”

Using blood samples that had been collected for decades by the BLSA, Carter described how age and prostate disease influenced PSA. “Based on his unique observations, he proposed new ways to interpret PSA levels, and specified intervals for testing that were the most informative,” says Walsh. As Chairman of the AUA’s Guidelines Panel, Carter developed recommendations for how all urologists should screen for prostate cancer.

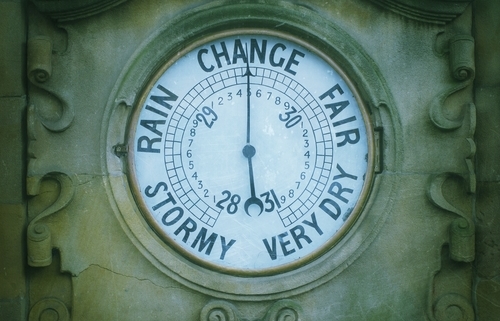

A Prostate Barometer

We discuss PSA in detail in chapter 4 of our book, but briefly: PSA should never be considered a one-shot, cut-and-dried reading. Instead, it’s like having a prostate barometer, so your doctor doesn’t have to wait for the PSA level to reach a magic number before acting. With PSA velocity, what matters is a significant change over time, and for this to be accurate, you need to have multiple PSA measurements taken in the same laboratory, because PSA measurements can vary slightly from lab to lab.

The level of change depends on your PSA number. For men with a PSA greater than 4, an average, consistent increase of more than 0.75 ng/ml over the course of three tests is considered significant. Let’s say that over 18 months, your PSA went up from 4.0 to 4.6 to 5.8. Clearly, something’s going on here.

But what if your PSA is less than 4? Walsh says: “Because we now realize that men with PSA levels as low as 1.0 may have cancer,” guidelines have been established for PSA velocity in these men, too: In these men, work by Carter and colleagues suggests, any consistent increase in PSA is alarming, even an increase as small as 0.35 ng/m. a year. They also found that many years before a man’s prostate cancer was diagnosed, when his total PSA levels (as opposed to more complex PSA readings, such as a free PSA test) were still low, a PSA velocity of greater than 0.35 ng/ml a year predicted who would later die from prostate cancer. If you have a PSA between 1 and 4 and it is consistently rising faster than about 0.4 ng/ml a year, you should get a biopsy.

What Should My PSA Be for My Age?

Be aware: 15 percent of men with a PSA level lower than 4 have prostate cancer, and 15 percent of these men with cancer have high-grade cancer, the aggressive kind that needs to be treated. That’s why we say in the book: “There is no safe, absolute cutoff above a PSA level of 1.0 at which a man can rest assured that he is not at risk of harboring a high-grade cancer. Thus, what probably is going to matter the most in the future is your PSA history.” Get that baseline PSA level in your early 40s, or at age 40 if you have a family history of prostate cancer, of cancer in general, or if you are African American.

Then, depending on the baseline level – whether you are above or below the 50th percentile for your age – take a repeat PSA test every two to five years. If you are in your 40s and your PSA level is greater than 0.6 ng/ml, or if you are in your 50s and your PSA is greater than 0.7, you should have your PSA measured at least every two years. If your PSA is below this percentile, you may be able to wait as long as five years for the next test. These are Carter’s numbers. In another study, of a larger group of men, urologists Stacy Loeb of New York University and William Catalona of Northwestern University found the comparable numbers to be 0.7 for men in their 40s and 0.9 for men in their 50s.

So, if you’re 50 and you have a PSA of 2.5, for example, and your doctor says it’s low, that doctor is wrong. It’s actually high for 50. It could be prostatitis, or benign prostatic enlargement (BPH). But it could also be cancer, and you need to get it checked out. A good next step would be to check the free PSA, with a test such as the Prostate Health Index (PSA has various forms in the blood, and these “second-tier” PSA tests can help tell whether it’s more likely to be higher because of BPH or cancer.) The higher the free PSA, the higher the likelihood that you are free of cancer, as Carter says. The numbers from studies vary, but one free PSA cutoff is 25 percent. If your free PSA is higher than that, your PSA is more likely to be elevated because of BPH than it is of cancer. If your free PSA is lower than 25, you are more likely to have cancer.

So, basically, to sum up: You can’t just look at a PSA number and know very much at all. It’s like looking at a Most Wanted photo and saying, “That guy looks guilty,” or “He has kind eyes! He’s probably been framed! He’s no criminal.” No self-respecting detective would ever try to get a warrant based on appearance. You investigate first. This is why you study PSA, watch what it does, and if it’s going up, check the free PSA, with a “second-tier” PSA test such as the Prostate Health Index (PHI); you also may need a biopsy. Don’t just give it a free pass after one test because “the number’s low.”

In addition to the book, I have written about this story and much more about prostate cancer on the Prostate Cancer Foundation’s website, pcf.org. The stories I’ve written are under the categories, “Understanding Prostate Cancer,” and “For Patients.” As Patrick Walsh and I have said for years in our books, Knowledge is power: Saving your life may start with you going to the doctor, and knowing the right questions to ask. I hope all men will put prostate cancer on their radar. Get a baseline PSA blood test in your early 40s, and if you are of African descent, or if cancer and/or prostate cancer runs in your family, you need to be screened regularly for the disease. You should start at age 40. Many doctors don’t do this, so it’s up to you to ask for it.

©Janet Farrar Worthington

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] Hopkins urologist who dedicated his career to studying PSA and who came up with the concept of PSA velocity, asked this question using data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging […]

[…] PSA Velocity: It’s Not the Number, but What It Does! – Vital Jake says: November 9, 2019 at 1:53 pm […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!