Prostate MRI: What Does My PI-RADS Score Mean?

Do you have prostate cancer? Answering that question is usually a multi-step process, with each step bringing another key piece of evidence to the puzzle.

Step 1 is the screening PSA test, which may or may not be accompanied by a rectal exam (we can call that Step 1a.) The trouble with the rectal exam is that it rarely catches cancer as early as the PSA blood test. That’s because it takes a while for prostate cancer to reach the point of being palpable (able to be felt by a doctor’s gloved finger). The rectal exam used to be the major way prostate cancer was diagnosed, but today, the PSA test offers the gift of time: it can detect prostate cancer years earlier than the rectal exam. So let’s just put the rectal exam, well, behind us for now, and concentrate on what to do next if you have an elevated PSA. (For what your PSA number should be for your age, please see this post.) Your doctor may order a repeat PSA, and if that, too, is elevated, or if the PSA has risen by more than 0.75 ng/ml (please see this post on PSA velocity) in a year, then:

Step 2 is… a prostate biopsy? No! As we have discussed on this website and in the book, a biopsy is invasive, it’s expensive, and there’s a risk of infection if you have the transrectal approach (instead of the better and newer transperineal approach, discussed here). Also, if you have the standard TRUS (transrectal ultrasound)-guided biopsy, prostate cancer is more likely to be missed. Ultrasound is simply not as good as MRI at showing suspicious areas in the prostate; an MRI fusion biopsy combines two forms of imaging (MRI and ultrasound) to get a better picture. Here’s a fun fact: Each needle core of a prostate biopsy samples only 1/10,000th of the prostate! As I said in the book, it’s like looking with a needle in the haystack. So doctors need all the help they can get to target suspicious areas of the prostate.

But we’re still not ready to pull the trigger on biopsy.We need more information. Step 2 is a second-line blood or urine test, such as a 4K score or PHI (prostate health index) test, discussed here. These tests look for cancer biomarkers and are designed to answer this question: Is my elevated PSA coming from clinically significant cancer – the kind that needs to be treated – or is it coming from BPH, benign enlargement of the prostate?

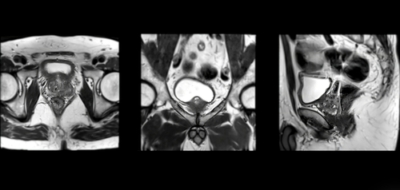

If the second-line test suggests clinically significant cancer is present, then Step 3 is… a biopsy? No! It’s prostate MRI. As we mentioned above, MRI can find cancers that ultrasound misses. Just look at this man’s story; by the time his cancer was diagnosed, after several years of a rising PSA and no answers, he had scar tissue within the prostate from multiple inconclusive TRUS biopsies, including saturation biopsies. The man’s poor prostate was a pincushion. Then he got an MRI, which spotted a suspicious area of his prostate; the man underwent an MRI fusion biopsy, his cancer was found, he had surgery, and at age 48 he was cancer-free.

So this is Step 3: prostate MRI, and as the 2018 landmark PRECISION study showed, the use of MRI before biopsy and MRI-targeted biopsy is “superior to standard transrectal ultrasonography-guided biopsy in men at clinical risk for prostate cancer.” In the study, clinically significant cancer was found in 38 percent of men in the MRI-targeted biopsy group, as compared to 26 percent in the standard TRUS biopsy group. Another bonus: only 9 percent of men in the MRI-targeted biopsy group turned out to have clinically insignificant cancer (which doesn’t need treatment immediately, and maybe won’t ever need it), as opposed to 22 percent of men in the standard biopsy group.

Step 4 is the biopsy, but we are going to stay in Step 3 for now.

The PI-RADS Score

A lesion in the prostate is not always caused by cancer. Infection or BPH can cause suspicious-looking areas in the prostate, too. Thus, radiologists have come up with the PI-RADS grading scale, which estimates how likely it is that a man with a lesion has prostate cancer. The PI-RADS scale goes from 1 to 5. Scores of 1 or 2 mean that there is no suspicious lesion, or that findings are consistent with BPH.*

*Let’s put a pin in this, no biopsy pun intended. We will come back to low PI-RADS scores in a minute.

A PI-RADS score of 3 means there’s an intermediate risk of prostate cancer, and this should trigger a biopsy.

A PI-RADS score of 4 or 5 means the lesion has a high or very high risk of being cancer.

The lower the PI-RADS score, the greater the likelihood that you won’t have cancer found on a biopsy, or if you do, that it will be insignificant. The higher the PI-RADS score, the greater the likelihood that you have significant cancer that needs to be treated. Using data from the PRECISION trial, your odds of having significant cancer found are: 12 percent if you have a PI-RADS score of 3; 60 percent if you have a PI-RADS score of 4; and 83 percent if your PI-RADS is 5.

So: if my PI-RADS is 1 or 2, am I off the hook? Not necessarily. Like every single diagnostic test for prostate cancer, MRI is not perfect, and low-grade cancer – lesions that only contain Gleason pattern 3 (for 3 + 3 =6, or Grade Group 1) – often don’t show up. This is because these slow-growing prostate cancer cells don’t look that obviously different compared to normal prostate cells.

Here is where PSA density can help provide clarity. PSA density is the PSA score divided by the volume of the prostate (which is determined by TRUS or MRI). The lower your PSA density (lower than 0.1), the lower your risk of having prostate cancer. If your PSA density is higher than 0.15, you have a higher risk of being diagnosed with Grade Group 2 (Gleason 7) or higher cancer. Even this may not need to be treated immediately.

Here’s a gratuitous note about MRI: I had an MRI to look at a tendon in my thumb and learned that I am really, really claustrophobic. It was an older machine, incredibly loud, and the technicians doing the test were playing this awful music in the tube with multiple F words. I couldn’t think, I couldn’t even pray coherently or form two sentences together in my head because of this stressful music and the loud banging noise of the machine. For some reason, they couldn’t get a good image and it took nearly 90 minutes. I got through it, but it was one of the worst, most panic-inducing things I ever did. If you are claustrophobic, talk to your doctor! It may be possible for you to go into the machine feet first, which would be great – at least your head wouldn’t be in the tube. It may be that your MRI is one of the newer generations, which are less like a torpedo tube and are, blessedly, more open. Or, as Weill Cornell Medicine urologist Jim Hu, M.D., M.P.H., who provided expert opinion on our diagnosis and staging chapter in the book, suggested, your doctor may prescribe a valium to help you relax in there. There’s no shame: if you need it, you need it.

In addition to the book, I have written about this story and much more about prostate cancer on the Prostate Cancer Foundation’s website, pcf.org. The stories I’ve written are under the categories, “Understanding Prostate Cancer,” and “For Patients.” As Patrick Walsh and I have said for years, Knowledge is power: Saving your life may start with you going to the doctor, and knowing the right questions to ask. I hope all men will put prostate cancer on their radar. Get a baseline PSA blood test in your early 40s, and if you are of African descent, or if cancer and/or prostate cancer runs in your family, you need to be screened regularly for the disease. Many doctors don’t do this, so it’s up to you to ask for it. Note: I am an Amazon affiliate, so if you do click the link and buy a book, I will theoretically make a small amount of money.

© Janet Farrar Worthington

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!